Evolution of Personality: Environmental Variation

Evolution of Personality: Environmental Variation

In last week’s blog post, I addressed the evolutionary genetics of personality and the genetic contributions to variation in personality traits. In this post, I would like to examine a different phenomenon, namely how the same genes can lead to different non-random variation in personality. If we want to understand how traits work as motivations, we need to understand how they evolved. Let’s briefly review some very simple models of how variation can link to genetics. In one model, variation in personality is due simply to people having different combinations of genes: People with gene A tend to be extroverts, while people with gene B tend to be introverts. This kind of model could represent what biologists call an obligate adaptation (a gene causes a trait in a fixed manner). However, people with the same genes may develop very different personalities if they are put in the same environment, through what is referred to as facultative adaptations (genes create mechanisms which develop in different ways in different environments, or different genes are turned on in different environments). Facultative adaptations are like “if-then” rules, as everyone tends to have the same genes; but if they develop in one environment, they create one characteristic (say, extraversion), and if they develop in another environment, they lead to another characteristic (say, introversion).

Let’s look at an example of specific variation to see how it could be explained by each of these models. In 2008, Schaller and Murray published a paper that explored the relationship between disease prevalence in the environment and personality traits within the population. They were particularly interested in investigating sociosexuality, extraversion and openness as all of these can confer some social benefit (reproductive, cooperative, etc.) but also increase risk of contracting communicable diseases (since increased social interactions means increased number of chances of contracting a disease). In other words, there is a cost/benefit tradeoff when it comes to disease avoidance that is revealed by psychological responses.

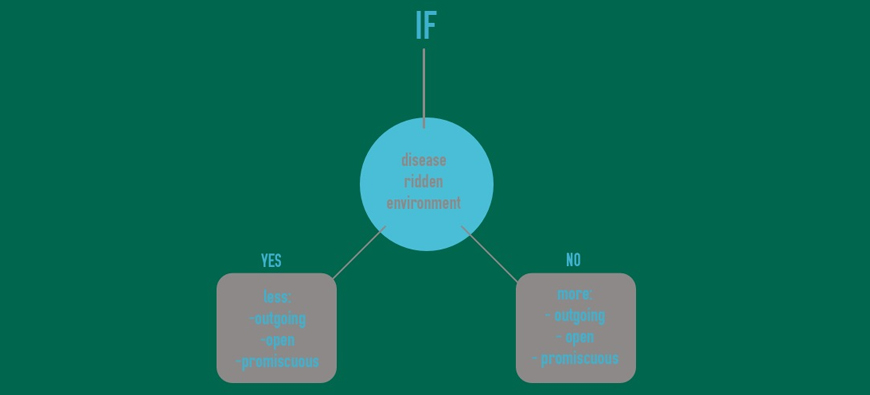

Consistent with their hypotheses, the authors found a negative correlation between all three aforementioned traits and disease prevalence, even after controlling for life expectancy, economic development status, cultural sense of individualism, and climate: aspects of people’s environment (e.g. increased disease prevalence) is indeed having some sort of impact on personality (e.g., people become less extraverted and open). Schaller and Murray point out there are a few different ways that such an effect could be explained in terms of evolution, but perhaps the most interesting is as facultative adaptations for coping with one’s local environment - simple rules like “if you find yourself in a disease-ridden environment, then you should be less outgoing, open and promiscuous.”

In another recent intriguing study, Lukaszewski and Roney (2011) found the trait of extraversion varies with physical attractiveness and strength. They reason that the benefits of being extraverted are easier to obtain for attractive and strong people, and argue that extraversion is a facultative adaptation and is genetically heritable at least in part because attractiveness and strength are genetically heritable. This fascinating finding indicates how genetic variation and facultative adaptations work together as non-mutually exclusive possibilities to lead to the strategic motivations we refer to as personality traits.

People often ask whether traits are nature and nurture, and this burgeoning research program demonstrates the flaw in that framework. Personality traits, like everything, are a complex mix of genes and genetic variation developing in different environments. They result from an interplay of genetic variance, and facultative adaptations to optimize how a person behaves given his or her specific environment and set of genes. All of this just reinforces that traits can be viewed as akin to behavioral strategies. Trait profiles are not random and they influence behavior along predictable dimensions. Being able to understand some of the environmental and other situational factors that go into the development of unique and individual personality identities is crucial to understanding the motivations behind many behaviors.